Christmas celebrates the coming of Jesus to offer forgiveness and peace with God to all who put their trust in him but what we perceive to be Christmas tradition in the UK owes much to Dickens. Somewhere in the last century the UK lost the plot, lost sight of the reason for Christmas, in favour of commercialising the message of hope and good will.

Christmas celebrates the coming of Jesus to offer forgiveness and peace with God to all who put their trust in him but what we perceive to be Christmas tradition in the UK owes much to Dickens. Somewhere in the last century the UK lost the plot, lost sight of the reason for Christmas, in favour of commercialising the message of hope and good will.

So why do we give presents at Christmas? The Bible presents Jesus coming to earth as God’s gift to humanity: ‘he will save his people from their sins’ (Matthew 1:21). The Bible consistently stresses the need to share the love of God with others, irrespective of race or religion, to care for the sick, the needy and ‘to love your neighbour as yourself’ (Mark 12:31), a message Dickens interpreted in A Christmas Carol, adding snow, ‘Bah humbug’ and improbable good cheer 🙂 .

Dickens celebrates Christmas as a beacon of hope in a grey industrial world, a world which feels remote from our own yet resonates clearly with it: ‘factory jobs and crowded cities of Victorian England … We can identify with Scrooge in his miserliness, yet also long for his redemption … The message of Christmas remains that the babe in the manger on Christmas morning was God’s “unspeakable gift” to the human race.'(Dr Jim Eckman).

Dickens celebrates Christmas as a beacon of hope in a grey industrial world, a world which feels remote from our own yet resonates clearly with it: ‘factory jobs and crowded cities of Victorian England … We can identify with Scrooge in his miserliness, yet also long for his redemption … The message of Christmas remains that the babe in the manger on Christmas morning was God’s “unspeakable gift” to the human race.'(Dr Jim Eckman).

Christmas – what the cartoon didn’t tell you

The first Christmas led to terrrifying bloodshed. Jesus came to bring peace between God and man but Herod (the political King of the Jews) ‘gave orders for his men to kill all the boys who lived in or near Bethlehem and were two years old or younger’ (Matthew 2:16) in an attempt to kill the young Jesus. Joseph and Mary fled to Egypt until Herod died so the young Jesus was in effect a political refugee.

Jesus didn’t come as an earthly prince and live in a palace – famously Mary ‘laid him on a bed of hay because there was no room for them at the inn’ (Luke 2:7). Out of interest the stable, donkeys, sheep etc so beloved by children’s nativity plays (and department store windows) don’t feature in the biblical text. The three kings don’t either, although ‘wise men’ do. As Clint Archer points out, ‘We tolerate the poetic inaccuracy of “We three kings of Orient are” because it rolls off the tongue better than “We indeterminable number of Gentile scholars of Persia are.”’ What’s significant is that the wise men were invited to see Jesus ie he came for everyone, not just the Jews.

Christmas, Presents and Dickens

Dickens saw the hypocrisy in a culture that celebrated Christmas but which largely ignored the inconvenient poor and needy. His social satires remind the reader with biting clarity of the need to live out the values of love, charity and peace with one’s neighbour every day. Christmas was a shared cultural reference point in Victorian England so it was an effective symbol for Dickens to use but his message, like that of the biblical text, does not restrict itself to one day.

If you’d like to read A Christmas Carol it’s available online here free courtesy of the excellent Gutenberg project.

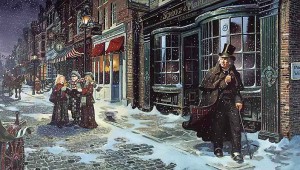

The following, including the image, is taken from Dr Jim Eckman’s article, ‘Charles Dickens and the Message of Christmas’, which can be read in full here:

For over 150 years Charles Dickens’ story of the miserly, miserable Ebenezer Scrooge and his three ghosts has been a regular Christmas tradition throughout Western Civilization. Indeed, even Hollywood has fueled this tradition by producing more than 15 feature productions of “A Christmas Carol.” Why is this story so powerful, so gripping and such a staple of the Holiday season? The answer lies in understanding the author, Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens is arguably the most influential novelist in the English language. It was his Christmas stories and his struggle with Christianity that dominated much of his life and permeated his writings. The ghosts of Christmas past, present and future haunt Scrooge throughout Christmas Eve night, as they expose all of his sins and shortcomings. He comes to terms with his greed and selfishness as “the squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous” miser. In short, Scrooge is regenerated, born again, into a generous, compassionate, loving man who rescues Tiny Tim from death, and becomes one “who knew how to keep Christmas well.” Christmas day becomes a reassuring antidote to the factory jobs and crowded cities of Victorian England. Today, we are far removed from Victorian England. But perhaps that is why we love the story so. We can identify with Scrooge in his miserliness, yet also long for his redemption. The message of Christmas is that God understands our miserly, selfish human condition and provides our redemption through His son, Jesus. The message of Christmas remains that the babe in the manger on Christmas morning was God’s “unspeakable gift” to the human race.